In the first post in this series, USA Court Statistics: The Numbers That Define the Justice System, we examined the scale and composition of the U.S. court system. State and local courts handle roughly 66 million cases each year, most of which are low-level matters, such as traffic violations, municipal code offenses, and minor misdemeanors.

That scale matters because small breakdowns, when repeated millions of times, produce large systemwide consequences. One of the most important of those breakdowns is failure to appear.

Where failures to appear actually occur

Failures to appear do not occur evenly across the court system. They are concentrated in the same low-level cases that account for the bulk of the court caseload.

Recent research from the Pew Charitable Trusts (2025), analyzing North Carolina data, found "higher rates of nonappearance for less serious charges, such as misdemeanors or traffic violations," compared with felonies. This inverse relationship between case severity and failure to appear is consistent across jurisdictions.

Before New York City's court reforms, research published in Science (2020) found that approximately 40% of defendants issued minor summonses (for offenses such as open container or disorderly conduct) failed to appear. In contrast, more serious felony cases typically have FTA rates in the 15-20% range, according to the most comprehensive national study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (though that data is now nearly two decades old).

This pattern is intuitive. Low-level cases often involve confusing paperwork, long delays between citation and court, limited access to legal guidance, and competing demands, such as work, childcare, or transportation. More serious cases usually involve attorneys, pretrial supervision, and clearer consequences.

When even a 15-20% failure-to-appear rate applies to millions of low-level cases, the result is a massive number of missed court dates each year.

What the national data shows

The most recent national analysis comes from the Prison Policy Initiative and Jail Data Initiative, which reported in January 2026 that at least 1 in 8 jail bookings (13%) are related to failure to appear. Approximately half of those, roughly 546,000 bookings nationally, involved only FTA charges with no new criminal offense.

Additional recent studies confirm this pattern:

-

Douglas County, Kansas (2017-2021): Failure to appear accounted for 24.2% of total pretrial bookings, with 40% of FTA bookings involving traffic cases

-

North Carolina (2019-2021): In the two counties studied, failing to appear on a misdemeanor was the number one reason people were sent to jail

These findings reveal that failures to appear drive jail admissions even when no new criminal activity has occurred.

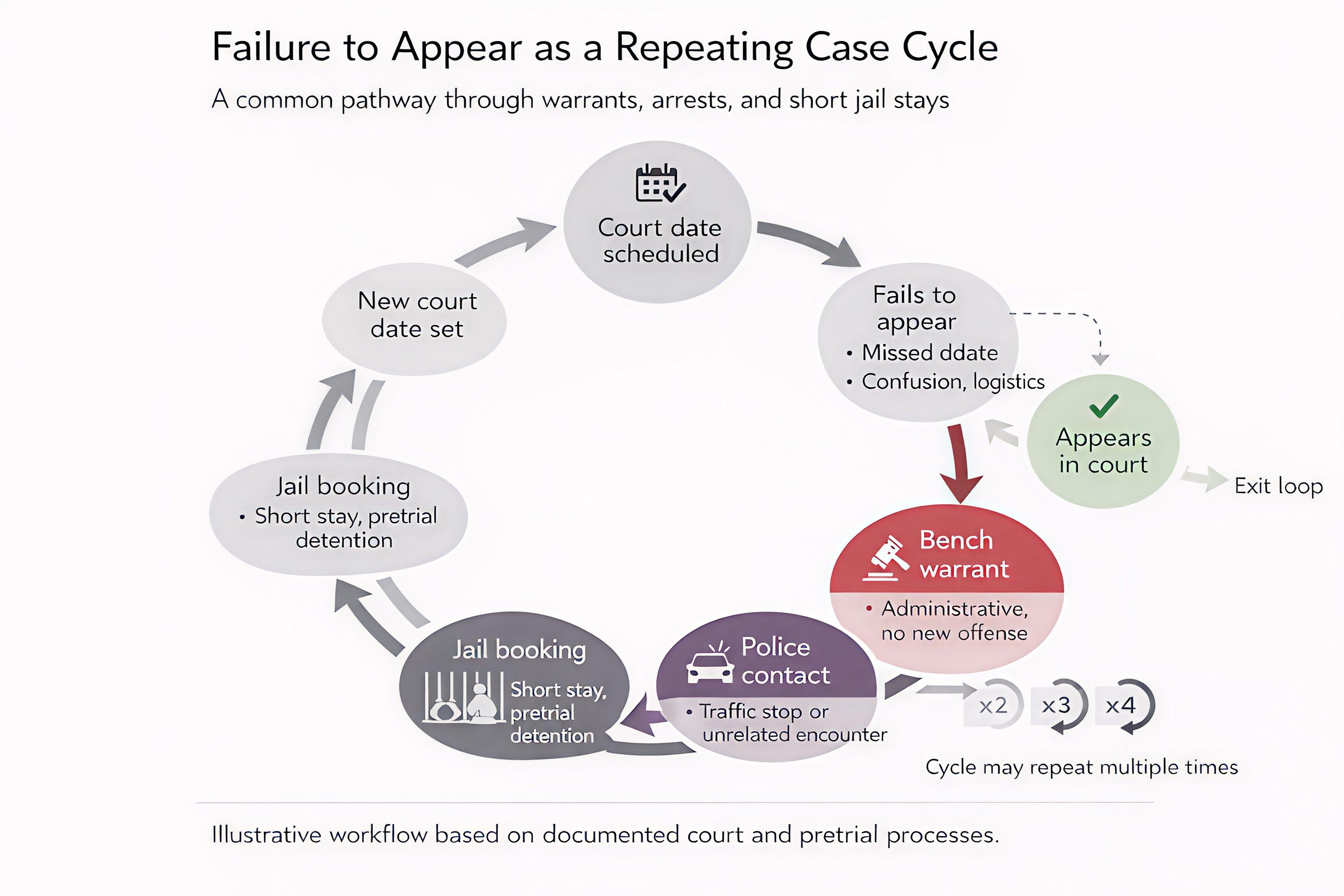

What happens after a missed court date

In most jurisdictions, a missed court appearance triggers a bench warrant. A judge issues a bench warrant for failure to appear or to comply with a court order, not for a new criminal offense.

Bench warrants typically remain active until they are cleared and do not expire on their own. Over time, this leads to substantial backlogs of outstanding warrants. While comprehensive national data is limited, jurisdiction-specific numbers illustrate the scale:

-

Harris County, Texas, had 50,247 outstanding warrants as of March 2022, with a monthly warrant inflow of 6,000 (double the pre-2019 rate).

-

As of 2016, an estimated 7.8 million outstanding warrants existed nationwide, a figure Justice Sotomayor cited in Utah v. Strieff and one that researchers noted likely underestimated the true total.

Research consistently shows that bench warrants account for the majority of outstanding warrants in most jurisdictions and that the vast majority stem from missed court dates in low-level cases rather than from new criminal conduct.

Once a warrant is issued, enforcement responsibility shifts to law enforcement. When a person with an outstanding warrant comes into contact with police (often during a routine traffic stop or unrelated encounter), the warrant serves as the basis for the arrest.

The most rigorous research on this pattern comes from the Data Collaborative for Justice at John Jay College, analyzing 2019 data:

-

In St. Louis, Missouri, 14% of all arrests were made solely to enforce bench warrants, with no new charge filed. An additional 25% of arrests involved at least one warrant and a new charge.

-

In Louisville, Kentucky, approximately 19% of arrests were warrant-only.

Analysis of underlying offenses in St. Louis showed that, among warrant-only arrests, 67% stemmed from ordinance violations (primarily traffic), 13% from misdemeanors, and 20% from felonies.

After arrest, jail booking often follows, even when the original case involved a low-level offense and posed no immediate public safety risk. The person may remain in jail for days or weeks awaiting a court hearing, only to be released with a new court date. This outcome could have been achieved with a phone call or text message without arrest or incarceration.

Why does the problem compound instead of resolving

Failure to appear has compounding effects because the system is designed to respond to noncompliance rather than to prevent it.

Bench warrants accumulate over time. A single missed court date can remain unresolved for years. Analysis from the Data Collaborative for Justice found that individuals arrested with at least one bench warrant in St. Louis had an average of 3.7 to 4.8 warrants per arrest, depending on demographics. In Louisville, the average was 1.7 to 2.1 warrants per arrest. This concentration means that although millions of warrants exist, they're not evenly distributed. A relatively small number of individuals account for a disproportionate share.

Fragmentation exacerbates the issue. In regions with many municipal or county courts, individuals may hold warrants from multiple jurisdictions. Law enforcement agencies become de facto warrant servers for dozens of courts, spending significant time enforcing administrative orders rather than responding to new criminal activity.

Jails experience this as churn. As the Prison Policy Initiative documented, roughly 13% of jail bookings nationally are related to failure to appear. These stays consume jail capacity, disrupt lives, and rarely resolve the underlying causes of nonappearance. A 2022 Pew Charitable Trusts analysis found that in 2019, people admitted to jail for misdemeanor charges typically stayed fewer than 9 days. These short but frequent admissions create a significant operational burden.

What the data does not support

Despite widespread assumptions to the contrary, recent evidence does not support several common beliefs about failures to appear.

First, failures to appear are not primarily acts of intentional evasion. The most comprehensive recent research comes from Lake County, Illinois (2023), which conducted 50 in-depth interviews with people in custody for bench warrants. The study found the following:

-

68% faced life responsibilities and challenges: managing mental health, homelessness, serving as a primary caregiver (60% of the sample), and managing work (58% were employed)

-

54% faced logistical and technical barriers: living in another county with limited transit, unreliable transportation, no computer for virtual court, and address issues preventing receipt of notices

-

36% were navigating more than one major barrier domain simultaneously

-

28% reported that attending court would put their basic needs (food and shelter) at risk

Complementary behavioral research from New York City (2020) identified four key psychological barriers: forgetting court dates as weeks pass, overweighing immediate hassles while ignoring consequences, misperceiving lost wages and fines, and misunderstanding social norms around court attendance.

Second, most outstanding warrants do not involve violent offenders. In St. Louis in 2019, 67% of bench warrant arrests were for ordinance violations (primarily traffic), 13% for misdemeanors, and only 20% from felonies. For Black individuals, nearly 75% of outstanding bench warrants were tied to traffic offenses. In March 2022, Harris County, Texas, reported that of its 50,247 outstanding warrants, only 703 were for murder and 4,833 for aggravated offenses. The rest were lower-level matters.

Third, arrest and incarceration are inefficient tools for addressing administrative noncompliance. Research from the Brennan Center for Justice (2019) found that governments spend $0.41 for every $1 collected through criminal justice fees and fines. One New Mexico county spent $1.17 to collect every $1, resulting in a net loss. This is 121 times more expensive than IRS tax collection.

These conclusions follow directly from how warrants, arrests, and jail admissions break down by case type across jurisdictions.

What actually works

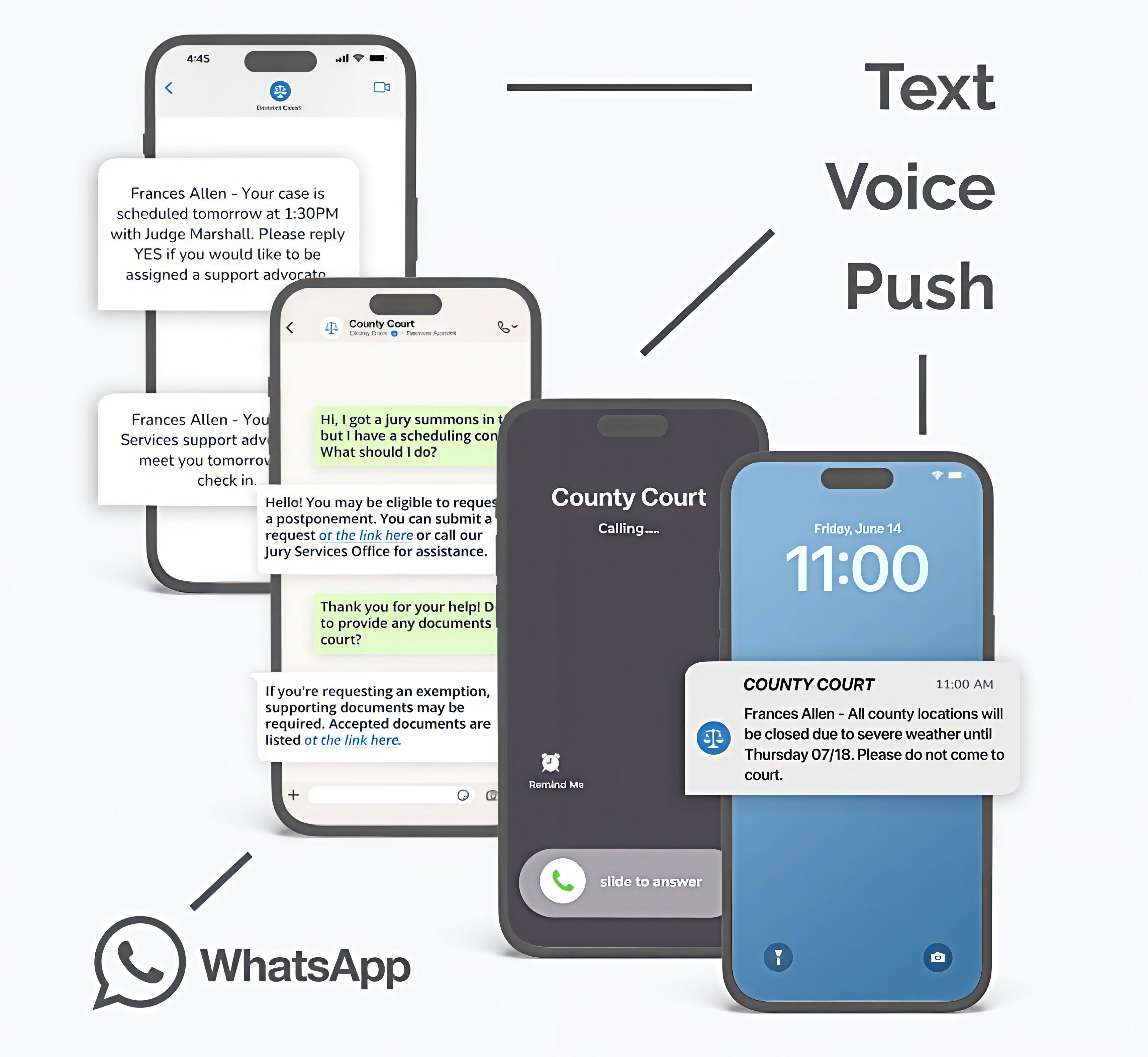

The most robust recent evidence points to a straightforward solution: court date reminders.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 12 studies with 79,255 participants found that people who received reminders were approximately 35% less likely to fail to appear. The analysis concluded that "court date reminders effectively reduce failures to appear across studies, so they are an inexpensive tool for jurisdictions seeking to implement pretrial reform efforts."

Recent jurisdiction-specific results include:

-

New York City (2020): Text reminders combined with redesigned court forms reduced FTA by 36% on low-level summonses

-

Santa Clara, California (2025): Text reminders reduced FTA by about 20%

These interventions cost minimal amounts. Text messages cost less than $0.01 each while preventing arrests, jail bookings, and warrant backlogs.

Why this matters for the rest of the system

Because the court system operates at such a scale, even modest failure-to-appear rates generate large numbers of warrants, arrests, and jail bookings. A system that processes tens of millions of low-level cases cannot absorb small inefficiencies without downstream consequences.

When 15-20% of people miss court in low-level cases, and each missed appearance generates a bench warrant that may remain active for years, the math becomes overwhelming. The Prison Policy Initiative's January 2026 finding that 1 in 8 jail bookings is connected to failure to appear (roughly 546,000 bookings annually) illustrates the scale of this problem.

Failures to appear are the hinge point. They connect court volume to enforcement activity and jail use. Understanding how and where they occur is essential to understanding why warrants accumulate and why jails experience so much administrative churn.

The next question, then, is not whether failures to appear matter. The data makes that clear.

The next question is why they happen so often in the first place and what the system does or does not do to prevent them. That is where the next entry in this series will focus.

Sources

National Data and Statistics

-

Prison Policy Initiative and Jail Data Initiative, "How many jail stays are due to missed court dates?" (January 2026)

-

Pew Charitable Trusts, "States Underuse Court Date Reminders" (May 2025)

-

Bureau of Justice Statistics, "Pretrial Release of Felony Defendants in State Courts" (2007)

-

Pew Charitable Trusts, "Jail Admissions Have Fallen, but Average Length of Stay Is Up, Study Shows" (January 2022)

Warrant Enforcement Research

-

Data Collaborative for Justice, "Warrant Enforcement in Louisville Metro and the City of St. Louis from 2006–2019" (December 2020)

-

Data Collaborative for Justice, "Warrant Arrests in the City of St. Louis, 2002–2019" (December 2020)

-

Data Collaborative for Justice, "Examining Warrant Arrests in Jefferson County, Kentucky: 2006 to 2019" (December 2020)

-

Harris County Office of County Administration, "Violent Persons Warrants Task Force" (March 2022)

Barriers to Court Appearance

-

Justice System Partners, "Understanding Court Absence and Reframing 'Failure to Appear'", Lake County, Illinois (2023)

-

Fishbane, Ouss, and Shah, "Behavioral nudges reduce failure to appear for court", Science (2020)

Cost and Effectiveness Research

-

Brennan Center for Justice, "The Steep Costs of Criminal Justice Fees and Fines" (2019)

-

Zottola et al., "Court date reminders reduce court nonappearance: A meta-analysis", Criminology & Public Policy (2023)

About Greg Shugart

Director of Government Relations

Greg Shugart brings over 30 years of public sector experience to the eCourtDate team, with a background in court administration, criminal justice reform, and government operations. He previously served as Criminal Courts Administrator for Tarrant County, Texas, where he led statewide-recognized initiatives in pretrial modernization, court communications, and system efficiency. Greg now contributes to eCourtDate’s strategy and partnerships, helping agencies implement technology that improves access, compliance, and trust in the justice system.