In the previous post in this series, Failure to Appear Is the Hinge Point in the Court System, we showed how missed court dates trigger a chain of bench warrants, arrests, and jail churn. At scale, even modest failure-to-appear rates have significant downstream consequences for courts, law enforcement, and jails.

That analysis naturally raises the next question.

Why do people miss court in the first place?

The answer matters because how the system explains failures to appear determines its response to them.

Most failures to appear are not acts of defiance.

Failures to appear are often framed as willful noncompliance. From the court's perspective, a missed date is a choice. According to the docket, the individual failed to appear.

But decades of court research and behavioral science point to a different conclusion. Most failures to appear are not intentional evasion. They are the predictable result of confusion, miscommunication, competing obligations, and human error.

The most comprehensive data on this comes from a 2023 Lake County, Illinois, study based on in-depth interviews with 50 people in custody for bench warrants. The findings reveal the reality behind missed court dates: 68% of participants were managing life responsibilities and challenges, including mental health diagnoses, frequent moves, homelessness, primary caregiving duties (60% were primary caregivers), and work responsibilities (58% were employed). 54% faced logistical and technical barriers: living in another county with no reliable transit, unreliable cars and suspended licenses, lack of computer access for virtual court, and address instability that prevented receipt of notices. Critically, 36% were navigating more than one primary barrier domain simultaneously.

Research synthesized by the Pew Charitable Trusts shows that nonappearance is concentrated in low-level cases, such as traffic, municipal, and summons-based matters, where people are least likely to have attorneys, supervision, or ongoing court involvement.

In other words, failures to appear cluster where guidance is minimal, and the system assumes people will navigate complexity on their own.

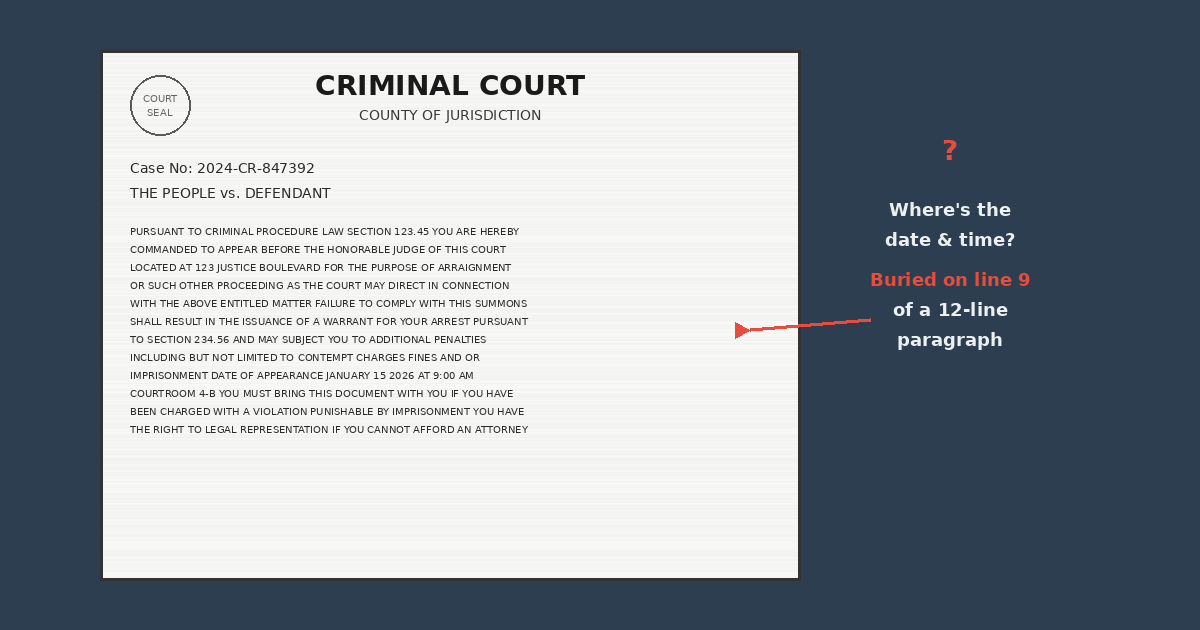

Court notices are easy to miss and hard to understand

For many people, the first and sometimes only court communication is a mailed notice. These notices are often sent weeks or months after a citation or arrest, to an address that may no longer be current. Even when delivered successfully, they are often written in dense legal language that assumes familiarity with court procedures.

The scale of this notification failure is striking. A Pew Charitable Trusts study based on interviews with civil debt defendants found that 25% reported never being notified of cases against them. Service documents were sent to outdated addresses or accepted by someone other than the defendant. One woman discovered $150 missing from her paycheck due to a garnishment stemming from a lawsuit of which she was unaware.

Before New York City redesigned its court summons system, approximately 40% of defendants who received minor summonses failed to appear. Behavioral research summarized by ideas42 showed that people routinely misunderstood basic information, such as the date, time, location, and the consequences of missing court. Some believed they could reschedule informally. Others assumed that payment resolved the obligation. Still others simply forgot after long delays.

None of these behaviors reflects an intent to avoid court. They reflect ordinary human responses to complex instructions delivered through unreliable channels.

The Lake County study found that 90% of participants were unaware that court reminder systems existed, even when opt-in programs were available. This awareness gap highlights a critical design flaw: requiring people to sign up for reminders assumes they know such programs exist and can navigate enrollment processes. When courts eliminate this barrier through automatic enrollment (with opt-out options), participation transforms. Ideas42's work with Colorado state courts demonstrates the impact: reminder usage increased by 300% in a single month after switching from opt-in to automatic enrollment, resulting in 34% fewer missed court appearances among recipients. Fewer than 1% of participants opted out, indicating that reminders are used.

Fear and experience create psychological barriers.

Ironically, fear of appearing can lead to nonappearance. In the Lake County study, 28% of participants reported that past court experiences were unhelpful, intimidating, or aggressive. Some feared arrest or jail if they appeared. Others felt overwhelmed by the process or found court actors confusing and difficult to understand.

The problem compounds for those with multiple pending cases. When people are arrested on warrants, they often have several outstanding warrants. In St. Louis, individuals charged with bench warrants averaged 3.7 to 4.8 warrants per arrest, meaning a single appearance could expose someone to multiple unresolved cases at once, amplifying the fear that keeps them from voluntarily appearing in the first place.

Research shows that structure, not motivation, drives appearance. Defendants represented by public defenders in Allegheny County were 20% more likely to be released without monetary bail, yet there was no statistically significant increase in failure-to-appear rates. Similarly, The Bail Project's national data across 29 jurisdictions show court appearance rates of 91-92% when clients receive support services, such as reminders and transportation. This demonstrates that assistance is more effective than financial incentives at securing appearances.

Time gaps and life constraints matter.

Failures to appear are also shaped by time. The longer the delay between an initial citation and a scheduled court date, the higher the risk of nonappearance. Memories fade, circumstances change, and contact information becomes outdated.

Studies reviewed by the Urban Institute document how work schedules, childcare responsibilities, transportation barriers, and financial instability contribute to missed court dates, particularly in low-level cases where court appearances directly compete with daily survival needs. In the Lake County study, 28% of participants reported that attending court would jeopardize their basic needs (food and shelter).

The vulnerability is most acute among homeless populations, who are 11 times more likely to be arrested than housed individuals are. In Austin, Texas, nearly 60% of the 10,529 citations issued for homeless-related offenses resulted in bench warrants. Text reminder systems that work for housed populations fail this group: in one study, only 35% of texts were successfully delivered to homeless individuals, compared with 55% for housed residents.

From the system's perspective, these barriers are often treated as excuses. From a behavioral standpoint, they are predictable trade-offs.

The system assumes perfect compliance in an imperfect world

Courts assume that once notice is given, compliance will follow. When it does not, the system responds with enforcement tools such as warrants and arrests.

But that assumption rests on a fragile foundation. It assumes:

-

Notices are received

-

Notices are understood

-

Dates are remembered

-

Logistics are manageable

-

Life disruptions do not intervene

When any of those assumptions fail, the system interprets the result as noncompliance rather than as a communication breakdown.

This helps explain why failures to appear are far more common in cases with limited court contact and far less common in cases involving attorneys, supervision, reminders, or repeated communication. The difference is not about motivation. It is structural.

Why this distinction matters

If failures to appear are primarily about defiance, then warrants and arrests are logical responses. If they are mainly about communication and logistics, then enforcement becomes a costly and inefficient substitute for prevention.

The system's focus on defendant nonappearance becomes particularly striking when measured against its own performance. A University of Virginia and University of Pennsylvania study of Philadelphia courts over 10 years found that system actors failed to appear at a rate of 53%. In contrast, the defendants' failure-to-appear rate was only 19%. Police officers failed to appear in 31% of subpoenaed cases; victims in 47% (69% for domestic violence cases). This reframes failure to appear as systemic dysfunction rather than as defendant failure.

Yet the system responds very differently to these equivalent behaviors. When defendants fail to appear in court, warrants are issued, and arrests follow. When system actors fail to appear in court, cases are continued or dismissed. Enforcement is one-sided.

Tulsa County estimates it spends approximately $1.2 million annually to incarcerate people for failures to appear: 15-day average stays that typically result in nothing more than a new court date. As shown in the first two posts in this series, the system currently relies heavily on reactive measures. Missed court dates generate warrants. Warrants generate arrests. Arrests generate jail bookings. The underlying cases often remain unresolved.

Understanding why people miss court does not excuse nonappearance. It explains it. An explanation is a prerequisite for designing systems that work at scale.

The next post in this series will examine what happens when courts change how they communicate. Across jurisdictions and study designs, the evidence shows that when notice improves, appearance improves. The remaining question is not whether these approaches work but why their adoption remains uneven.

Sources:

-

Justice System Partners, "Understanding Court Absence and Reframing 'Failure to Appear'", Lake County, IL, 2023 (https://justicesystempartners.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/SJC-Lake-County-Getting-to-Court-as-Scheduled-Reframing-Failure-to-Appear.pdf)

-

Pew Charitable Trusts, "State Courts Play a Key Role in American Life" (https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2024/10/state-courts-play-a-key-role-in-american-life)

-

Pew Charitable Trusts, "Why Civil Courts Should Improve Defendant Notification," March 2023 (https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2023/03/why-civil-courts-should-improve-defendant-notification)

-

ideas42, "Reducing Unnecessary Arrest Warrants & Jail Time: NYC Summons Redesign"(https://www.ideas42.org/project/nypd-summons-redesign/)

-

ideas42, "(Un)warranted Newsletter: Why auto-enroll for court reminders? Because it works!" January 27, 2026 (https://ideas42.org)

-

Urban Institute, "Removing Barriers to Pretrial Appearance" (https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104177/removing-barriers-to-pretrial-appearance_0.pdf)

-

Slocum et al., "Warrant Arrests in the City of St. Louis, 2002–2019," Data Collaborative for Justice, December 2020 (https://datacollaborativeforjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020_12_15_Warrant-Reports-Press-Release.pdf)

-

Graef, Lindsay, Sandra G. Mayson, Aurelie Ouss, and Megan Stevenson, "Systemic Failure to Appear in Court," University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 172, 2023 (https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/penn_law_review/vol172/iss1/1/)

-

Anwar, Shamena, Shawn Bushway, and John Engberg, "The Impact of Defense Counsel at Bail Hearings," Science Advances, Vol. 9, Issue 18, May 2023 (https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP70066.html)

-

The Bail Project, "Cash Bail Data: A Closer Look" (https://bailproject.org/data/unlocking-the-truth/)

-

Vera Institute of Justice, "Arrest Trends for People Experiencing Homelessness," August 2020 (https://www.safetyandjusticechallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/homelessness-brief-web.pdf)

-

Chohlas-Wood, Alex, et al., "Automated reminders reduce incarceration for missed court dates: Evidence from a text message experiment," Science Advances, Vol. 11, 2025 (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx7483)

About Greg Shugart

Director of Government Relations

Greg Shugart brings over 30 years of public sector experience to the eCourtDate team, with a background in court administration, criminal justice reform, and government operations. He previously served as Criminal Courts Administrator for Tarrant County, Texas, where he led statewide-recognized initiatives in pretrial modernization, court communications, and system efficiency. Greg now contributes to eCourtDate’s strategy and partnerships, helping agencies implement technology that improves access, compliance, and trust in the justice system.